By Cheryl Yin

In 2014, I was overwhelmed with my big move to Cambodia. As a linguistic anthropology PhD student, I had to conduct long-term ethnographic fieldwork as part of my dissertation project. This meant I had to live in a community for 1-2 years in order to gather data, which would be the basis of my dissertation. As a Cambodian American from Long Beach, CA, the largest Cambodian community in the United States, I wanted to investigate changes to the Khmer (Cambodian) language in the aftermath of the Khmer Rouge, so I needed to live in Cambodia for a couple years to collect data. Before leaving, a former classmate found out I was going to Cambodia and asked if I could deliver something to her brother who had just been deported there the year before: a care package with clothes and snacks. Although I knew about the deportation issue in the Cambodian American community — that many Cambodian American refugees who were green card holders in the United States were being deported to Cambodia due to their criminal record — I did not know that my fieldwork would force me to confront this issue head on and make me reflect on my childhood upbringing.

Memories in Long Beach

Growing up in Long Beach, I was surrounded by the vibrant Cambodian community. I ate kuyteav at Hak Heang restaurant, celebrated Cambodian New Year at El Dorado Park, and my legs fell asleep while sitting on the floor while Buddhist monks chanted for hours at the pagoda. I also saw glimpses of a community that was still suffering from trauma and a generation of youths who struggled with intergenerational trauma. My family and many of my neighbors continued to depend on government assistance to survive. I saw large families of eight or 10 squeeze into two-bedroom apartments, sharing beds and turning the living room into an extra bedroom. My elementary school classmates and I qualified for free lunch. Some of my peers had trouble keeping up in school. Some had parents with gambling or drinking problems.

My academic path slowly diverged from my neighborhood peers when I was allowed to attend a middle school 7 miles away from my home in a more middle-class neighborhood on the other side of Long Beach. While I benefited from programs intended to help underprivileged students attain educational success, it wasn’t until I graduated from college that I began to critically examine my life alongside the lives of my hometown friends and ask why those programs did not benefit everyone in my community. My childhood peers were just as smart as me. Why did these educational programs select a few lucky students, but neglected to help my other peers?

Finding home in Cambodia

This question continued to haunt me when I kept bumping into deportees in Cambodia. In fact, the first person I saw after exiting Phnom Penh’s airport in 2014 was one. “Hey, are you Cheryl?” a man with a large build asked in an American accent. “Your aunt told me to pick you up.” I said OK and followed him out to the parking lot where a relative was watching our interaction. Apparently, they were playing a prank on me and wanted to know how I would react to a stranger coming up to me. My relative was surprised how calm and believing I was, asking if I would really get into a car with a random stranger. As someone who can read people pretty well, the stranger’s flawless American accent (Cambodians have trouble pronouncing my name, “Cheryl”) along with his large build, shaved head, and casual dress indicated he was a Cambodian American. As my aunt and uncle retired to Cambodia after living in the United States for 27 years, I was willing to believe this man was acquainted with them. My gut reaction was correct. Charles* was my uncle’s blood nephew while I was my aunt’s blood niece, so we were cousins by marriage. He grew up in the Inland Empire region of California. After a drug offense and time in prison, Charles was a convicted felon, so he saw his deportation to Cambodia as a fresh start, believing he would have had trouble finding a job in the United States anyway due to his felony. My aunt and uncle helped him out when he arrived in Cambodia.

During my two years in Cambodia, I slowly became acquainted with the deportee community. After giving Bun* his sister’s care package, he took me to the Returnee Integration Support Center (RISC) and introduced me to other deportees. RISC was the first stop for many deportees, providing a place for them to stay as they got settled and found direction. Although I was the only woman during my visit, I felt right at home because they reminded me of Long Beach. It wasn’t long before I realized how small the deportee community in Cambodia was. I kept running into Cambodian American deportees in Phnom Penh and Battambang during fieldwork, though many were reluctant to share that information at first due to the stigma. My friend Sophea Phea, for example, was an English teacher at a private school. I was surprised when I opened Facebook one day and read an article where she revealed that she was one of the few women who had been deported and had left behind a son in the United States. While I saw the resiliency of the deportee community, I also saw a lot of heartache as deportees talked about the family they left behind in the United States and shared their difficulties adapting to life in Cambodia.

Strengthening my voice through LAT

I returned home in January 2017, ready to write my dissertation and complete my PhD, but my experience with returnees haunted me. In spring of that year, I saw an announcement that SEARAC was accepting applications for their Leadership and Training (LAT) program and that one possible focus would be on the unjust deportation of Southeast Asian Americans (SEAA). I was hesitant to apply because I am not a very politically active person. I do not like to talk about politics. I am not the kind of person to attend demonstrations. I have no background on public policy. Despite my reservations, I decided to still apply and I was fortunate that SEARAC accepted me. Still, I worried that I would not be able to contribute thoughtfully in the program.

All of my worries washed away on Day 1 of the LAT in Washington DC.

“It was the first time I was in a space that was so intentional on setting the right tone, on honoring everyone’s experiences, and on making sure we tell culturally relevant stories.“

After one training session where a SEARAC staffer gave a brief overview of the deportation of Southeast Asian Americans (SEAAs), which has disproportionately impacted Cambodian Americans, I overcame my fear and raised my hand to add my own thoughts. I was nervous while holding onto the microphone, but I spoke up and shared that I met many Cambodian American deportees in Cambodia. I wanted to make sure people knew that many deportees do not speak Khmer very well and most do not know how to read or write in Khmer. They are not “returning” to their homeland because they have no connection to Cambodia. In fact, Cambodia is a foreign country to them and many struggle to find ways to fit in and survive.

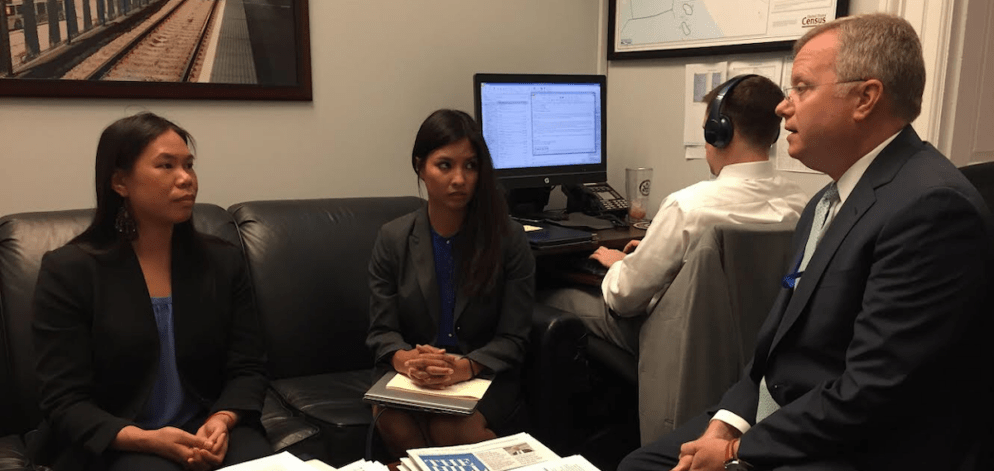

Before attending the LAT program, I never knew I could make an appointment and talk to my state representatives and senators. I was pessimistic and did not think my voice mattered. SEARAC not only made an appointment for each and every one of us to meet with our local representatives, but they also trained us on how to make the most of our meeting. I could not have asked for a better mentor than my SEARAC mentor Souvan Lee, and I could not have asked for better groupmates than Nancy Yeang and Tina Chinakarn. Souvan, Nancy, and Tina kindly listened to me read a draft of my statement to my hometown representative, US Rep. Alan Lowenthal (CA-47). I remember staying up late the night before our Capitol Hill visit, drafting my statement—which may have been a bit too long, but what can I say? I’m an academic! When the time came, I ended up reading my statement to Scott Walker, a Pearson Legislative Fellow in Lowenthal’s office. Despite my wordiness, Scott sat there and listened to my every word as I shared how my family were Cambodian refugees who resettled in Long Beach, CA, and how Cambodian American deportees were refugees trying to survive in the United States. Scott shared that he grew up in Fresno and that he had many Laotian and Hmong friends, so he understood the challenges SEAA refugees faced. Because SEARAC trained us to make sure to have an “ask,” I asked Scott if Rep. Lowenthal would make a statement condemning the deportation of Southeast Asian American refugees. I remember he nodded and said that was a great idea. (Rep. Lowenthal would go on to introduce the Southeast Asian Deportation Relief Act in 2022.)

When the LAT program came to a close, I remember feeling so rejuvenated to have connected with so many wonderful people. I was also moved by the personal stories that circulated during the LAT program. Some stories came from SEAAs who were about to be deported before they were granted a stay. Some stories came from family members fighting to stop their loved ones’ deportations. Other stories were from the 1.5 or 2.0 SEAAs who faced intergenerational trauma as they tried to make sense of their identity and belonging. Throughout the LAT, I cried tears of sadness, but also tears of happiness to have found a community of people who have made it their mission to uplift the voices of SEAAs. I have since stayed in touch with a few of my LAT cohort members.

From advocacy to leadership

After my LAT experience, I had many opportunities to give pedagogical talks and create lesson plans (see page 105) for K-12 educators on any topic related to Southeast Asian studies so that they may diversify their curriculum. I chose often to spread awareness on the unjust deportation of SEAAs.

I supplement SEAA data about immigration, education, healthcare, and mental health with personal anecdotes from my childhood growing up in Long Beach. Not only do I bring awareness to the deportation issue, but I also provide possible next steps on how audience members can advocate for SEAAs. K-12 educators often come up to me after my presentations to tell me that they had no idea the United States was deporting Cambodian Americans and how shocked they were that crimes like public urination and possession of marijuana were deportable offenses.

Continuing the journey of fighting for change

With the LAT experience under my belt, I have continued to advocate for deportees. I am currently on the nonprofit board of Tiny Toones, a school in Cambodia founded by a Cambodian American deportee named KK. Originally, KK helped at-risk youths stay out of trouble by teaching them breakdancing, but it eventually grew into a community center where students are provided a safe place to learn and get an education. Sophea, whom I met in Cambodia, was one of the few deportees who was granted a pardon. When she returned to the United States, not only was she getting her college degree, but she created the nonprofit board for Tiny Toones in the United States this year because they are in dire need of funds after funders left during the pandemic. While creating the nonprofit board, Sophea asked me if I would be interested in serving as the secretary. I enthusiastically said yes! With our tax-exempt status, we have held several fundraising events, from Cambodian New Year festivals to a campaign on Facebook in honor of Sophea’s birthday. While speaking to potential donors, we not only talk about the positive impact Tiny Toones has had on the students, but we also highlight the deportation issue that brought people like KK and Sophea to Cambodia in the first place. For those in the United States who would like to make a tax-deductible donation to Tiny Toones, you may do so by looking up Tiny Toones on Zelle (nonprofit@tinytoones.org), PayPal (nonprofit@tinytoones.org), and Venmo (@TinyToonesCambodia). Donors outside of the United States may use Global Giving.

I can finally see myself as an advocacy leader because SEARAC’s LAT created a pathway for me to find my voice. Thank you!

For more blogs in our #LATSpotlight series celebrating 25 years of SEARAC’s Leadership and Advocacy Training Program, see:

Applying leadership and advocacy skills — for life by Va Her

Speak your truth, even when your voice shakes by Lasamee Kettavong

Purely in community by Cat Bao Le